Django being created way before type hints were a thing in Python, it wasn’t designed with

typing support in mind. External projects raised typing support at a decent level, but are

mainly tied with mypy. In this article, I will go briefly over

the current state of the Django typing ecosystem and provide a hopefully viable alternative

to the current mypy plugin.

TL;DR: django-autotyping creates custom stubs

for your application, providing a reliable alternative to the Django mypy plugin

and enhancing the Django development experience.

The current state of Django typing

Without any external tool or external type definitions (a.k.a. type stubs), the type checker will do its best to infer the correct types,

but will fail in most cases, and you often end up with Anys.

The most common (and probably annoying) example appears when dealing with models and fields:

from django.db import models

class Blog(models.Model): ...

class BlogPost(models.Model):

name = models.CharField(

max_length=255,

)

blog = models.ForeignKey(

to=Blog,

on_delete=models.CASCADE,

)

When accessing attributes of this model at runtime, the database type is mapped to a Python type:

>>> type(blog_post.name)

#> <class 'str'>

>>> blog_post.blog

#> <Blog: My blog>

But without any further information, the type checker will not be able to infer these types, and will instead

understand name and blog as being instances of CharField and ForeignKey.

To overcome this issue, the TypedDjango organization provides type stubs along with a mypy plugin. Without going into much detail, our previous issue

with field types can be solved by specifying the base Field class as being generic over the Python type. By giving the correct type hints to the __set__ and __get__ methods of the Django field descriptors, type checkers can natively infer the correct attribute type, even

if a Field instance was defined initially on the model.

# By defining `Field` and `CharField` to be roughly equivalent to:

class Field(Generic[T]):

def __get__(self, instance: Model, owner: Any) -> T: ...

class CharField(Field[str]): ...

# blog_post.name will be correctly inferred as being `str`!

However, this will not be enough when dealing with related fields such as ForeignKey, as the actual __get__ return type depends on what the actual

foreign model is. To support this use case, we can define the __init__ method like this:

class ForeignKey(Field[T]):

def __init__(self, to: type[T], ...): ...

ForeignKey instances will now be parametrized on instanciation! Thus supporting all our fields specified in the BlogPost model.

When type hints are not enough

We saw previously that by making field classes generic, we could parametrize each field type with a specific Python type.

However, due to the nature of the relations between database models, we often face circular import issues when referencing models between files. To deal with this, Django supports passing a string representation of the model

(either "{model_name}" or "{app_label}.{model_name}"), and while supporting this use case could be feasible in other

type systems (such as TypeScript), there is currently no solution with the current Python typing features.

This is where the Django mypy plugin comes into play: it provides support for string references to models, together with a nice set of Django specific features (e.g. type checking for lookup queries, managers, settings, etc).

The drawbacks of using the mypy plugin

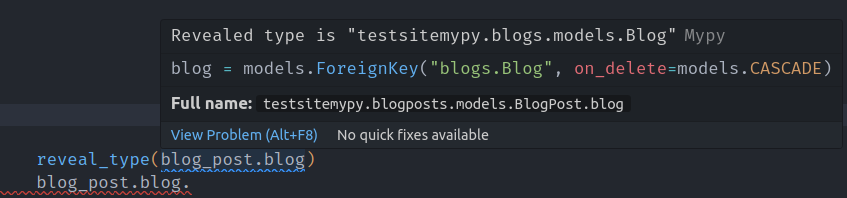

Using a type checker can be beneficial to catch errors that would usually result in unhandled exceptions at runtime. To get immediate feedback on these errors along with the inferred types of your code, the type checker can be hooked up in your IDE via a LSP integration (for VSCode users, this is what Pylance is essentially doing).

Does this mean we can get all the nice auto-completions and features provided by mypy and the Django plugin?

Not really. While LSP implementations for mypy are available,

they seem to be lacking features that I really enjoy as a VSCode/Pylance user 1. You do get the correct types from the mypy plugin, but you are missing all the highlights/auto-completions:

Dynamic stubs to the rescue

As pyright doesn’t provide any plugin ability, I needed to find a solution that would ideally:

- Be agnostic of any type checker, that is only using the existing Python typing logic.

- Avoid having to manually annotate your code.

To implement these lacking features, I created django-autotyping,

a tool that can also be used as a Django development application that provides the features described below.

The first idea that came to mind was writing a code transformer that would go over files and explicitly annotate fields where necessary. Using the previous code example, it would produce the following (assuming the two models live in different apps):

from typing import TYPE_CHECKING

from django.db import models

# Model is imported in an `if TYPE_CHECKING` block to avoid circular imports

if TYPE_CHECKING:

# Related model is imported from the corresponding app models module:

from project.blogs.models import Blog

class BlogPost(models.Model):

...

blog = models.ForeignKey["Blog"](

"blogs.Blog",

on_delete=models.CASCADE,

)

To implement this codemod, I’ve been using LibCST. The result was looking great, but still too verbose in my opinion 2, and it wasn’t taking nullable fields into account.

The second idea I had was writing custom stubs for the current project. Most type checkers (at least mypy and pyright) have the ability to specify a custom folder where type stubs can be found. By wisely crafting type definitions, it is possible to natively get the same features as the mypy plugin.

Going overkill with Literal and @overload

A smart feature available in type checkers is to add overloads

to the __init__ method of a class to influence the constructed object type. With the following:

# __set__ value type

_ST = TypeVar("_ST")

# __get__ return type

_GT = TypeVar("_GT")

class ForeignKey(Generic[_ST, _GT]):

@overload

def __init__(

self: ForeignKey[Blog | None, Blog | None],

to: Literal["Blog", "blogs.Blog"],

...,

null: Literal[True],

...

): ...

@overload

def __init__(

self: ForeignKey[Blog | None, Blog],

to: Literal["Blog", "blogs.Blog"],

...,

null: Literal[False] = ...,

...

): ...

# Each available model in your app will lead to two generated overloads.

You can get:

- Complete support for typed foreign fields, without any manual annotations

- Support for nullable fields

- Complete IDE support!

This “dynamic parametrization” of models is really powerful as it avoids having to explicitly parametrize type variables.

Thinking the other way around

We just saw it was possible to influence the parametrization of a class from the __init__ arguments, but

it is also possible to do the opposite: influence the arguments of a method depending on the actual class. Consider

the lookup query methods available on Manager and QuerySet instances:

T = TypeVar("T", bound=Model)

class Manager(Generic[T]):

...

@overload

def filter(

self: Manager[BlogPost],

name: str = ...,

name__icontains: str = ...,

# and more...

) -> QuerySet[T]:

Instead of the unhelpful filter(*args, **kwargs) signature, you actually get the available lookups for this model

(which can be of great help for beginners) 3.

There’s many places where this could be useful: the __init__ signature of models, various methods of querysets, etc.

Is this the perfect solution?

I would love to think it is. But there are still things to take into account.

Performance considerations

LibCST being mainly written in Python, generating stub files can get slow for bigger projects. Testing on a Django application with a hundred models or so, generating the necessary overloads for the foreign fields takes around 30 seconds.

Generating the stub files is something you only need to do after a Django migration though. If this becomes too much of an issue, I might have to consider switching to a faster AST/CST transformer (Ruff might be suitable).

Type checkers might also struggle to understand what’s going on. On the same Django project, pyright seems to be going fine, but I haven’t tested with mypy (which is known to be slower).

Dynamic stubs don’t solve everyting

Even if the generated dynamic stubs cover a lot of cases, explicit annotations are still required sometimes. Consider the use case of reverse relationships:

# On a blog instance, the related blog posts can be accessed:

blog.blogpost_set # Or with a custom attribute name, by specifying `related_name`

To make the type checker aware of this attribute, you have to explicitly annotate the Blog class:

class Blog(models.Model):

# `BlogPost` also needs to be imported, and the `Manager` class

# used might differ:

blogpost_set: Manager[BlogPost]

Fortunately, a codemod can actually handle this for you (which I’ve yet to implement).

django-stubs is still tied to the mypy plugin

Some parts of the django-stubs project are meant to work only with the mypy plugin. A fork named django-types was created a couple years ago, to make it easier to work with other type checkers. However, this fork is lagging behind.

However, there is currently some work ongoing to merge the projects back together and hopefully make django-stubs usable without the plugin 4.

For more details about how this can be used, you can follow the instructions on the django-autotyping repository (which is still very much in progress). Using the tool is just a matter of adding an app to your INSTALLED_APPS.

I believe there’s a lot to explore with dynamic stubs. This can also be extended to other projects that make heavy use of dynamic behavior.

While

pyright– the type checker from Microsoft used by Pylance – is open source, it does not provide plugin functionnality. Regarding Pylance, the implementation isn’t open source, so we can’t really extend it with the same features as the mypy plugin. Besides, the plugin features we are trying to implement fit at the type checker level, not the LSP. ↩︎And in reality not really playing well with

django-stubs. Django fields are actually defined with two type variables: one for the__get__type and the other for the__set__type. To be accurate, the codemod would have to transform our code toForeignKey["Blog | None", "Blog"]. Prior to Django 4.1, this would lead to runtime failures, asForeignKeydid not implement the__class_getitem__classmethod, so the codemod will have to explicitly annotate the field type toblog: models.ForeignKey["Blog | None", "Blog"] = models.ForeignKey(...). ↩︎The provided arguments are of course limited. For large models with foreign relationships, generating all the available lookups might not be possible or too overkill. It is also not possibe to take transforms into account. ↩︎